The crowd waits with the players below, all in formation, crouched into statues of potential energy. The centre looks left, then right. Finally, the snap. An explosion of movement ripples across the field. Dale Creighton, Western Mustangs’ all-star fullback, takes off in his headlong fashion. He lowers his head and charges through his opponents. When the play ends, he does not get up.

Dale E. Creighton was a gifted athlete, but his aggressive running style also led to 13 concussions on the gridiron. And in the 1950s, our understanding of concussions wasn’t what it is today. No one considered the long-term aftershocks. Years later, during retirement, Dale started forgetting things. His behaviour changed.

Thankfully, his family noticed these signs. Together, they embarked on a journey larger than any of them anticipated. Early intervention was an important step in diagnosing Dale’s frontotemporal dementia because it gave the Creightons time to prepare.

“We made a commitment to Dad’s ongoing care,” says Dale’s son, Matthew Creighton. “If there was a study Dad qualified for, we made sure he was involved.”

No treatment exists to slow or stop neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s and dementia. Furthermore, persistent injuries, such as the ones Dale sustained, can increase the risk of long-term neurodegeneration.

Dr. Elizabeth Finger, neuroscientist at London Health Sciences Centre (LHSC) and lead investigator for the Dale E. Creighton Brain & BioBank (DECBB), says those in her field are still in the discovery phase.

“There are many genetic and molecular pathologies that can give rise to neurodegenerative dementias,” Dr. Finger explains. “We’re trying to understand these changes.”

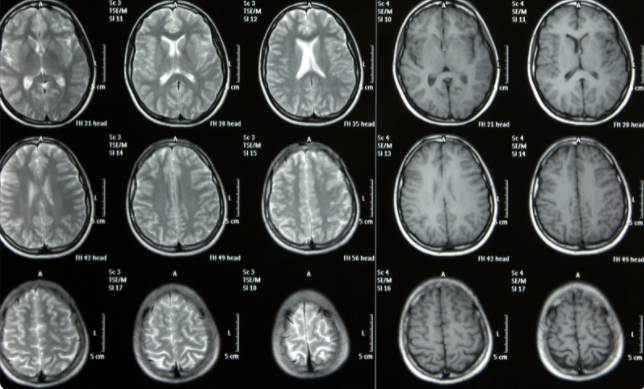

This notion gave way to the DECBB. A collaborative effort spanning years of conversation and strategic deliberation, the DECBB is designed for people wishing to contribute to science by donating a most precious resource: their brain. And for those who are willing and who qualify, the process of donating a brain can begin simply by visiting the DECBB online.

“London’s wealth of clinical programs related to neurodegenerative dementias helped the Creightons and I realize our part in facilitating the research and discovery of treatments for these devastating afflictions,” Dr. Finger says.

From international studies on improving our understanding of frontotemporal dementias, to local ones using innovative technology to profile abnormalities in afflicted brain tissue, DECBB is becoming a vital resource against neurodegenerative disorders. And for those who qualify, the process of donating a brain is as easy as visiting the DECBB online. When asked if he would donate his own brain, Matthew gives a resounding, “Yes!”

“Having two generations to study and compare would be pretty valuable in terms of continuing the clinical history,” he exclaims.

Sadly, Dale passed away in 2017. However, contributing the inaugural grey matter deposited for study is testament to who he was in life. Someone committed to his family and community; who considered himself fortunate regardless of the hurdles placed before him. Fitting then, that his lasting memory is dedicated to hopefully, one day, allowing others to keep their own.